We live in a critical time in history, when the decisions we take about every aspect of our life are crucial. The impact of our actions used to be just on ourselves and our entourage, big or small; nowadays the consequences are planetary.

If we want to avert catastrophic damage to the planet and our livelihoods, the call for action is very clear. We need to make changes to the way we live, how we travel to work, how we holiday, how we dress and what we eat.

The good news, for those who are fortunate to live in a free society, is that we can choose our course of action and make better choices going forward.

Are we making good use of our freedom of choice?

When we look at diet and food choices, the general answer to this question is no. Despite knowing what is right for us, we are continuing to choose bad diets that drive a global obesity epidemic and contribute to the risk of developing other health problems. We are seeing increasing levels of Type 2 diabetes, high blood pressure, and coronary heart disease to name but a few.

There has been a steady and inexorable growth of obesity in the world in the last 30 years: 4 out of 10 adults in the world are overweight, the same number indicates obese adults in the USA, and in Europe roughly 1 out of 4 adults is obese.[1]

These data are staggering, especially when confronted with data on malnutrition and disease, showing that in many countries under-nutrition and over-nutrition coexist in the same population, sometime in the same family.[2]

The evidence is clear: the world’s diet is bad for people’s health.

Dietary recommendations have been there for us to follow for many years in the form of food pyramids and eat-well plates, only to be ignored. One of the most researched and positive answers is: follow the Mediterranean diet!

Recently these recommendations have become even more pressing, when looking at the impact of the food system on climate change and the use of natural resources: food production, distribution and use account for 26% of global emissions, with the vast majority coming from agriculture and the use of land.[3]

Again, the answer is clear: both the EAT-Lancet report [4] and the WWF live-well plate [5] recommend a diet largely based on plant foods, fruit, vegetables, cereals and whole grains, a low amount of animal-based products, some fish and limited amounts of added fats and sugar. Plant based proteins from beans and pulses replace meat, which is not eliminated but roughly limited to one portion of red meat and two portions of white meat per week. Very similar to the Mediterranean diet, some would argue.

This would deliver healthy diets to the growing world population and ensure a sustainable food system with greatly reduced emissions, land, water, fertilizer use and biodiversity loss.

It is a no brainer. Why don’t we just do it?

In fact, changing behaviours is difficult, as food choices are most of the time not rational.

In other words, simply being aware of the issues and knowing what the data is telling us is still not enough to shift behaviours.

We need to better understand the mindsets of people and their decision making process, so that we can encourage them to choose a different course of action which is better for them. We need to design the right “choice architecture”. These concepts have been well documented and applied in many different domains [6], and famously led to the “Nudge Units” established by governments in several countries.

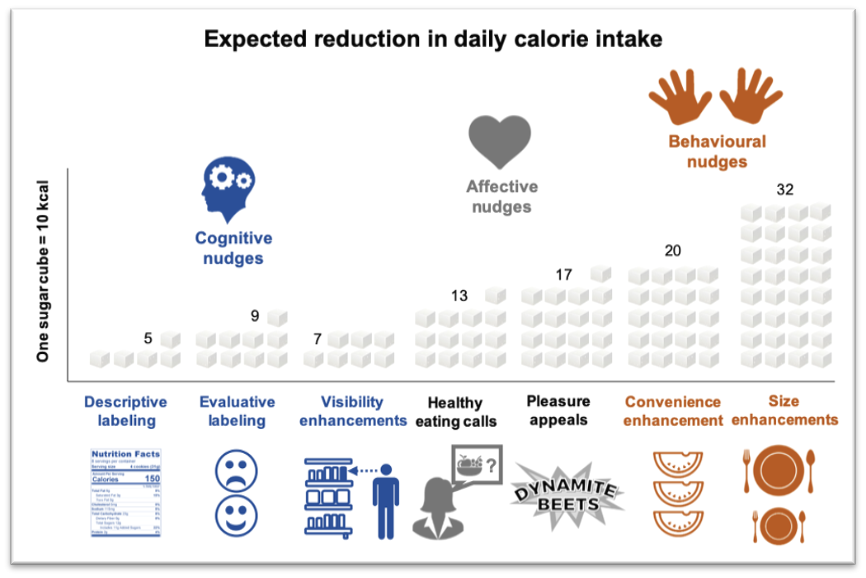

The applications of nudges to the use of food are very revealing. The effects are significant and quantifiable (see Figure 1).

Adapting the size of dishes is the most striking; simply put, fries in a small dish and vegetables in a large dish directly influence the amount people eat.

A good example of the application of the concept of choice architecture to food is the design of a restaurant menu.

The World Resources Institute published a comprehensive playbook of interventions to encourage diners to select more plant-rich dishes; amongst the most impactful are the presentation, layout and language used to design the menu. [8]

Does it really work?

Some of the quoted menu presentation interventions have been tested in a family hotel in an Italian beach resort, Lignano Sabbiadoro. The Hotel Smeraldo provides its dining clients with a menu of three choices for the starter and three choices for the main course. Traditionally the main course was presented in the following order:

- a meat dish,

- a fish dish,

- a third “simpler” choice based on eggs, cheese, cured meat, or vegetarian.

During the 2021 holiday season, the Hotel decided to make three changes to its menu:

- move the “simpler” choice from position 3 to position 1

- increase the times this choice is a vegetarian dish

- make an effort in the description of the vegetarian dish to increase the appeal from a taste, texture and authenticity standpoint. E.g., not just “omelette alle verdure”, but rather “omelette morbida con verdurine al profumo di tartufo”.

The initial results are very promising: the uptake of the vegetarian option has been very high compared to previous years. As a consequence of these changes the consumption of meat per customer in the restaurant has declined by 25% compared to last season, as measured by suppliers’ invoices. The environmental footprint calculations are yet to be carried out, but there is confidence that the hotel’s new menu has seen more of its clients choosing healthier and more sustainable options.

Right for their health, right for the planet

If you work in the food sector and are concerned about the dietary choices and behaviours of your clients and your employees, then use the power of choice architecture to influence them in making the right decision. Right for themselves, their health and the planet.

References / further reading

[1] H. Ritchie and M. Roser, “Obesity.” https://ourworldindata.org/obesity (accessed Oct. 19, 2021).

[2] B. M. Popkin et al., “NOW AND THEN: The Global Nutrition Transition: The Pandemic of Obesity in Developing Countries,” Nutr. Rev., vol. 70, no.1, 2012.

[3] J. Poore and T. Nemecek, “Reducing food’s environmental impacts through producers and consumers,” Science (80-. )., vol. 360, no. 6392, pp. 987–992, 2018.

[4] W. Willett et al., “Food in the Anthropocene: the EAT-Lancet Commission on healthy diets from sustainable food systems.,” Lancet (London, England), vol. 393, no. 10170, pp. 447–492, Feb. 2019.

[5] G. Kramer et al., “Eating for 2 degrees new and updated Livewell plates,” pp. 1–74, 2017.

[6] R. Thaler and C. Sunstein, Nudge – The final edition. Penguin, 2021.

[7] R. Cadario and P. Chandon, “Which healthy eating nudges work best? A meta-analysis of field experiments,” Mark. Sci., vol. 39, no. 3, pp. 465–486, 2020.

[8] WRI, “Playbook for guiding diners toward plant rich dishes in food service,” 2020. Available: https://www.wri.org/research/playbook-guiding-diners-toward-plant-rich-dishes-food-service.