In every newspaper, advertisement or political speech, plastic is now considered as the number one public enemy. We have already witnessed the terrible impact of plastic pollution on flora and fauna, and we are now seeing the consequences of micro and nano-plastic in our food chain. What remains unclear is what alternatives to plastic should we be using.

Some plastic products, like single-use items, can easily be substituted, yet plastic remains by far the most popular material used for packaging. Furthermore, it is expected that polymer production will only increase in the next few years.

Do we have alternatives?

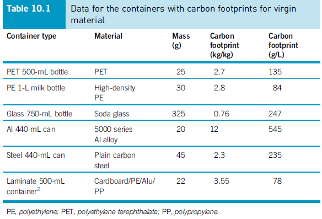

As a starting point it is important to understand whether we already have an alternative material to plastic. This year a retired professor from Cambridge University performed a Life Cycle Analysis (LCA) of several different packaging materials (1). LCA is a standardised methodology to assess the environmental impact across all stages of a product’s life. The results are surprising: laminate containers and plastic have the lowest carbon footprint per unit of volume, while aluminum and glass have the highest.

According to other research, “If all plastic bottles used globally were made from glass instead, the additional carbon emissions would be equivalent to 22 large coalfired power plants producing enough electricity for a third of the UK” (2).

Tetra Pak, the indisputable leader of laminate cardboard packaging for drinks, proposes to switch its packaging and abandon plastic. Most vegan dairy products are now packed in composite cartons and for many people Tetra Pak has become a symbol for sustainable packaging. Some companies are on board with Tetra Pak’s marketing campaign and, as an example, this month Alaska Airlines has announced that it will replace all its water PET bottles with carton packaging (3).

However, the materials used by Tetra Pak in their packaging are not without issues. Although the fiber pulp used to produce the packaging is derived from renewable resources, the final product is not made of recycled paper and originates from freshly cut trees. The packaging consists of composite paper, plastic, and aluminum layers, which are very difficult to separate for recycling. While the overall EU beverage carton recycling rate is around 51%, there are not that many facilities in Europe that can recycle such packaging. It is feasible to recycle the paper part, but the plastic and aluminum fractions are mostly incinerated for energy as it is not economically beneficial to recycle them. Lastly, the cardboard layer can only be down recycled, meaning that at the end of its life it can’t be recycled into beverage packaging but could be used to produce a pizza box (4). Therefore, despite a great marketing campaign by Tetra Pak and other producers, their packaging is not easy to recycle, and it should not be seen as the sustainable material it is claimed to be.

Plastic is the second-best material in terms of carbon footprint according to the LCA, as shown in Table 1. Many packaging companies still favour it because of its durability, its strength, and its weight. Many recyclers would prefer to deal with it because almost all types of plastic can easily be recycled, allowing it to become part of a circular economy. There are great examples of small-scale recycling facilities in Kenya, Uganda, Russia, Colombia, and other countries where people make roofing tiles, pavements and bricks of all types of recycled plastic. The biggest advantage of plastic compared to cardboard packaging is that it doesn’t need to be down recycled; a PET bottle will be recycled into a PET bottle about 10 times before it is down recycled.

What is wrong with plastic?

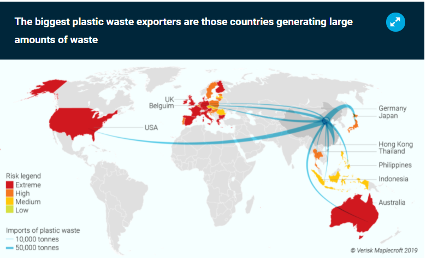

The problem is not with plastic itself, it’s with us. Instead of recycling it, we burn it, send it to landfills, export it to other countries or simply throw it away as litter. For many years developed countries have been sending their waste to China and other Asian countries where the infrastructure is not yet ready to cope with the increasing amount of plastic waste. China’s ban on waste imports means we export our waste to Eastern Europe, Russia, Latin American and other Asian countries in high volumes. This shows we haven’t addressed our habits or changed our behaviour; we have simply transferred the problems to another part of the world.

Main global plastic waste flows after China’s ban (5):

Developing improved recycling facilities is the best solution we could implement right now. According to research by the Imperial College, London (2) “If all plastic were recycled this could result in mean annual savings of 30 to 150 million tonnes of CO2, equivalent to shutting between 8 and 40 coal-fired power plants globally.” Not only would this be great for the environment, but opening recycling facilities will lead to new green jobs and additional revenues. It is not necessary to transport our waste to another part of the world when these facilities could be available locally. There is no need to open huge facilities, small plastic waste recycling facilities can have up to 20 employees, with initial investments of EUR 100-150k. We generate so much waste that this could be a thriving business.

So why are small entrepreneurs not rushing into this business? The main reasons are due to its low profitability and high competition with huge international companies. It is still cheaper to make plastic from virgin fossil fuels than from recycled plastic waste. Currently, according to the plastic waste makers index (6) two American companies (ExxonMobil and Dow) and a Chinese company (Sinopec) together account for 16% of all produced single-use plastic, and this will only increase to at least 30% in the coming years. Plastic makers rely so heavily on fossil fuels that only 2% of today’s global production comes from recycled plastic waste. Major banks (including HSBC, Barclays and Citigroup) along with the biggest asset managers (including Vanguard, BlackRock and Capital Group) are actively supporting polymer producers. There is no problem with plastic itself, but the problem lies in how we produce and dispose of it.

Can recycling be a solution?

It is unconceivable to keep supporting the production of plastic from fossil fuels instead of recycled waste and to keep exporting our waste to countries with poorer waste management facilities. There is no need to continue using valuable raw materials when we have enough plastic waste that could be recycled over the next decades. As a push towards ESG policies, plastic production coming from virgin fossil fuels should not be financed by banks and its producers should pay additional taxes, fees, and penalties, to disincentivise companies from using such materials.

Many governments urge the importance of plastic recycling and in 2018 European Commission set a 55% recycling rate for plastic. Recently, various international companies (including Coca-Cola, Unilever, Pepsi and Danone) have pledged to using only recycled plastic for their packaging. Such companies have the potential to partner with SME producers of recycled plastic and support them with loans, grants and sharing expertise. Small and medium scale plastic waste facilities can become a part of the plastic waste solution. Opening and operating such facilities require less investments and less human resources. Local waste can be recycled directly where it is generated instead of being transported over long distance which will help also reduce the CO2. Plastic waste can either be recycled for packaging or can become a new product, e.g., benches, roofing tiles, fences, etc. This will not only help fight the plastic waste but also increase the employment in the rural areas and local production.

Whether we continue to love or hate plastic, there’s one thing for certain, demand for recycled plastic will only increase in the future.

References and further reading

[1] Michael F. Ashby “Materials and the Environment” 3rd edition 2021 p.232

[2] Voulvoulis N., Kirkman R., Giakoumis T., Metivier P., Kyle C., Midgley V “Examining material evidence the carbon fingerprint” Imperial College London p.1

[3] Alison Fox “Alaska Airlines is eliminating all plastic water bottles on its flights” 3 November 2021

[4] Eunomia and Zero Waste Europe “Recycling of multilayer composite packaging: the beverage carton” December 2020

[5] Will Nichols ‘Where should the world’s waste go?’, 13 August 2019

[6] Minderoo Foundation ‘The plastic waste makers index’, 2021